Exploring Isle Royale National Park, “The Good Place”

A morning storm rolls in over Rock Harbor on Isle Royale's eastern edge.

Story and photos by Joe Rogers

Joe is a freelance travel writer and photographer based in Denver, Colorado. See more of his work at The Travelin' Joe or on Instagram.

Minnesota’s North Shore All-American Scenic Drive leads to a prime wilderness experience.

“Welcome to McCargoe Cove,” announces the ferry captain of the Voyageur II. Two deckhands leap into action, dropping fenders and tying off dock lines to secure the 65-foot vessel that brought us from Grand Portage, Minnesota, to the north shore of Isle Royale National Park, the least-visited national park in the Lower 48.

On the dock, a campground host logs my arrival and asks my expected destination for the night. “Daisy Farm campground,” I tell her as I sling my backpack over my shoulders. On my map, I quickly memorize today’s 8.4-mile route along three trails: East Chickenbone, Greenstone Ridge and Daisy Farm. On my 72-hour visit, I’ll hike roughly 15 miles to Rock Harbor, my longest trek with a weighty pack in a decade. As the boat’s diesel engines rumble back to life, I wave to the captain and crew and stride into the wilderness.

Isle Royale National Park, 300 miles from Minneapolis, rises from the cold, deep waters of northwest Lake Superior. The Ojibway named it Minong, or “the good place,” as the land was rich in copper, food and medicinal plants. Today, the park offers everything from kayaking, scuba diving and hiking to camping in untamed wilderness or relaxing at Rock Harbor Lodge on the island’s eastern edge. No cars are permitted, and because Isle Royale can be reached only by ferry, seaplane or private watercraft, the park remains as wild as it is remote.

The Voyageur II ferry arrives in Isle Royale National Park.

Split Rock Lighthouse is one of the most scenic locations on Minnesota's North Shore.

Driving the North Shore

My quest to reach Isle Royale started in Duluth, where I steered my rental car north on Minnesota State Highway 61, also known as the North Shore All-American Scenic Drive. Along the 145-mile journey, I made many worthwhile stops.

I toured Two Harbors Lighthouse, peering from an old watchman porthole as ships floated like apparitions on the horizon. In Gooseberry Falls State Park, 13 miles farther along, I dipped my bare feet in the refreshing water while photographing Upper, Middle and Lower Falls.

For half a century, Split Rock Lighthouse — just 6 miles up the road — provided safe passage to freighters carrying mined ore across Lake Superior. A little farther along, a boulder below Tettegouche State Park’s thunderous High Falls made for a misty, scenic lunchtime perch. Dessert included a birds-eye view of climbers on a vertical route at Palisade Head. Finally, Grand Portage National Monument provided a history lesson in living off the land, the North American fur trade and a critical 8.5-mile transportation route the Ojibway used for thousands of years.

Heeding locals’ culinary advice along the journey, I stopped at Russ Kendall’s Smoke House in Knife River to sample “the best smoked fish on the North Shore,” and bought a pound of brown sugar-cured lake trout. At Betty’s Pies In Two Harbors, I ordered seconds of the legendary bumbleberry pie. And in artsy Grand Marais, Sven & Ole’s pizza lived up to its reputation.

Then, I was off to Grand Portage, one of Minnesota’s two departure points to Isle Royale. A ferry also leaves from Grand Marais, and departure points in Michigan are Copper Harbor and Houghton.

High Falls is a must-see attraction at Tettegouche State Park.

Moose wade into a lake on Isle Royale National Park.

‘Earning’ the Wilderness

Those who hike and camp, or “earn it,” as one 20-year Isle Royale veteran reminded me on the ferry, must tote and collect water, pack out what is packed in and deal with changing weather patterns. “The deeper into the interior you go, the more cut off you are,” he said. Instead of a warning, for me that’s a tantalizing draw.

Four hours later, I reach camp and kick off my boots inside one of the first-come, first-served wooden shelters. Sweat drips from my forehead, collecting in small pools next to my clammy footprints as I set up my tent inside. Then I sit down and chug the last of my water. I’m drained and sore, but totally elated. Today’s trek, a perfect introduction to the park, took me past isolated lakes, floating bogs and downed paper birch. High ridges allowed views into Canada.

I saw far more wildlife — moose, beavers, red squirrels, rabbits, bald eagles — than people. As dusk settles over camp, I boil water for making dinner as I watch a sizable beaver shore up its handiwork in a nearby bog. Long after I’m finished eating, my neighbor’s work continues, even as I drift off to sleep.

A red squirrel stops to eat.

The author takes in the view along his backcountry hike.

A Return to ‘Civilization’

Boom! A roaring crack of thunder jolts me awake. I slide out of my sleeping bag and stand near the screen door. First comes a flash, then another deafening explosion. This time, the whole shelter shakes. With two days and just over 7 miles to go, I’ve got time, so I lay back down. Later, I hike east toward Three-Mile Campground with Rock Harbor Lighthouse off in the distance to my right.

At times, I execute a balancing act on the trail, teetering between wet logs and slick rocks while trying to avoid puddles and thick, sticky mud. After a while, I give up and tromp through it as though I’m 10 again. Time and again I recall my childhood — much of it spent outside — and I remind myself to slow down, to be quiet and to soak in every aspect of nature.

My return to these often-forgotten patterns bestows amazing gifts: hours alone on the trail and atop Mount Franklin, conifer forest aromas, shadow and light, wind and cooling rain. My wildlife encounters were the most memorable. I watched a trio of moose feed on aquatic grasses, rabbits nibbled grass at my feet as I too enjoyed a midday snack and I held a butterfly at arm’s length while it fluttered its wings. Each was a moment of harmonious coexistence and mutual trust.

When I reach Rock Harbor, park rangers are holding orientation for a new group of excited visitors. Some will head for a night’s stay at the 60-room lakeside lodge with two adjoining restaurants while others shoulder the weight of their packs while walking west. At camp, I run into people I met on the ferry. We set off to explore together this time, checking out everything from the dockside store to Stoll Memorial Trail. We share stories and laugh at the ease of returning to civilization again.

Later, over celebratory drinks, we bask in our individual adventures. Each is unique, as is any experience on Isle Royale for those who find their way to “the good place.”

Visitors learn about the fur trade at Grand Portage National Monument.

Related

Read more stories about national parks.

- Majestic Mountain Loop Family Fun

- Road Trip to Indiana Dunes National Park

- Cades Cove Scenic Drive is a Trip Back in Time

- Majestic Mountain Loop

- Road Trip from Denver to Glacier National Park

- Driving Through The Smoky Mountains: Planning Your Road Trip

- Isle Royale National Park

- Mountain Road Trips

- Weekend Getaway to Bryce Canyon National Park

- Visiting Glacier National Park in Winter

- Road Trip on Utah's Scenic Byway 12

- Road Trip to Big Bend National Park, Texas

- Visiting Washington's Olympic National Park in the Offseason

- Road Trip Through Central Oregon

- Day Trip to Dry Tortugas National Park

- Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park

- Washington’s North Cascades National Park

- Road Trips to National Parks in Winter

- Cascades Loop Road Trip

- Fall Foliage Road Trip in Road Trip From San Francisco to Yosemite

- Road Trip to White Sands National Park

- Road Trip to Saguaro National Park

- Petrified Forest National Park

- Cold Weather Photography Tips

- Mount Rainier National Park

- Road Trip to Acadia National Park

- Road Trip from Olympic National Park to San Francisco

- Colorado’s Great Sand Dunes National Park

- The Loneliest Road in America

- Road Trip to Death Valley National Park

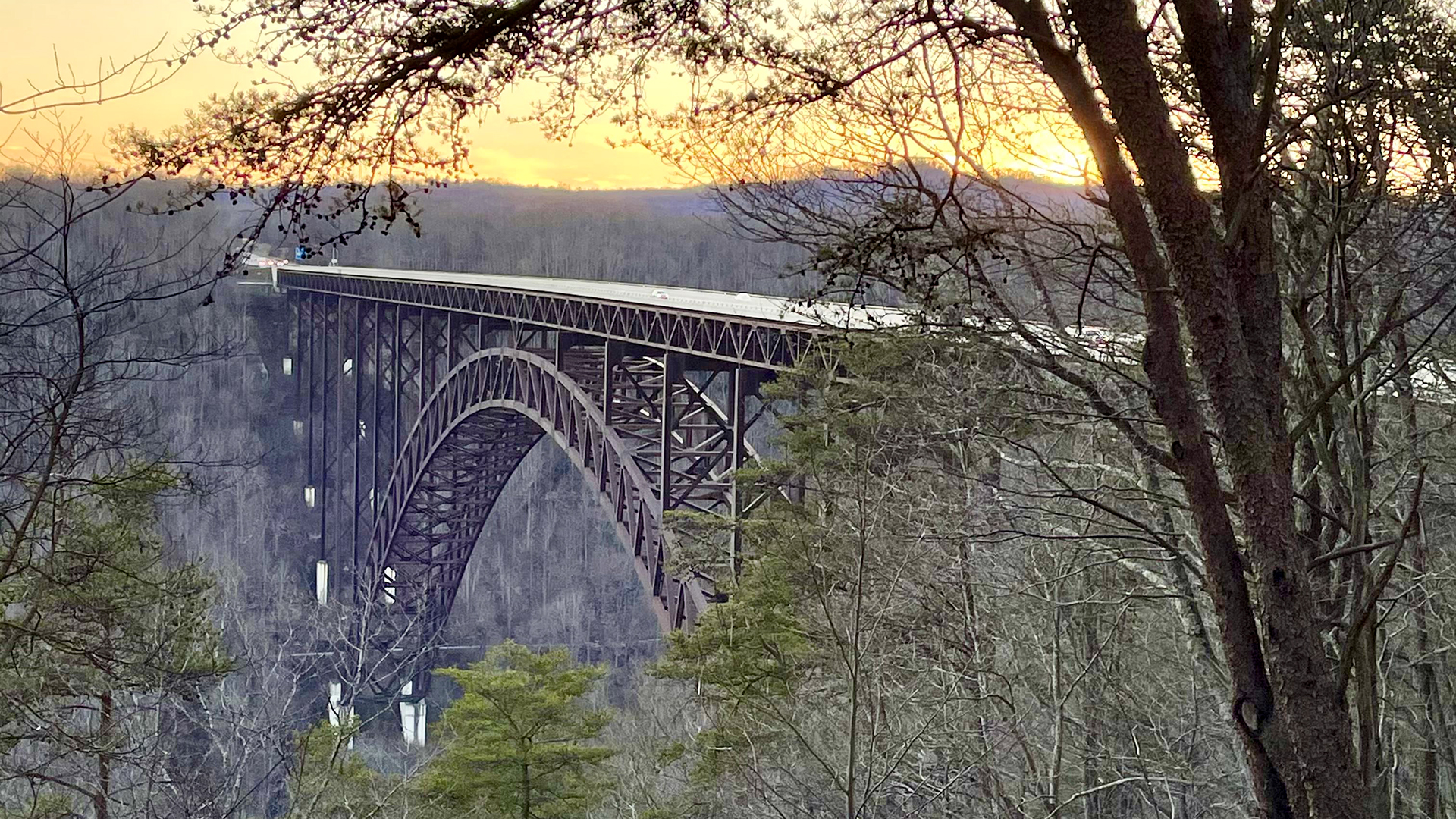

- New River Gorge National Park

- Things to Do in Hot Springs, AR on Your Next Getaway

- Road Trip to Dark Sky Parks in Utah

- Weekend Getaway to Yosemite National Park

- Plan a Road Trip to a National Park Near You

- Grand Canyon Hike

- National Park Tradition Renews Family Ties

- Road Trip to Five National Parks Near Los Angeles

- Yellowstone National Park in Winter

- Road Trip Through Northern California

- Rocky Mountain National Park Snowshoeing

- Great Smoky Mountains Waterfalls

- Grand Teton National Park

- Road Trip to Zion National Park for Artistic Inspiration

- Weekend Getaway in Joshua Tree National Park