Road Trip to See Whales

A humpback whale leaps out of the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Maui, Hawaii.

Story and photos by Patricia Corrigan

Patricia is a journalist, photographer and book author based in San Francisco.

A whale watcher dedicates nearly four decades to an unanticipated passion.

We’re on a boat, scanning the horizon, looking for a whale spout. Anticipation builds as we hang on to the rail, watching for what we’re told will look like a puff of steam from a busted radiator. If we miss that telltale sight, we may see a dark dorsal fin or the broad back of a whale. Suddenly, we see something in the water ahead. We cheer and grab our cameras.

“That’s a cardboard box,” the naturalist says.

That happened on my first whale-watching trip, almost 37 years ago out of Barnstable, Massachusetts. The trip got better — much better. After hearing the explosive sound of a whale’s exhalation, after watching half a dozen whales surface, swim and dive as though choreographed, and after viewing 12-foot-wide whale tails rise above and then sink below the water’s surface, I was hooked.

Whales travel through the oceans of the world, and though I lived in the Midwest at the time, I decided I would travel whenever possible to see whales in their natural habitat. Over the years, I’ve flown into numerous airports on both coasts of North America, rented a car, driven along scenic shoreline roads to a marina and boarded a boat. You can, too.

Watching whales connects me to nature, heightens my respect for the beauty and complexity of the planet and decreases my sense of self-importance. I feel humbled and exhilarated at the same time. And on every trip, in addition to seeing whales, I see something I’d never see on land — tiny jellies called by-the-wind sailors, a 1,500-pound ocean sunfish, or a tufted puffin bobbing in the waves.

Today some 15 million people go whale watching each year. I know I’m not the only one with a whale tail tattoo, but I like to think no one else whispers the whales’ Latin names to call them to the surface. It works for me!

Gray whales make an annual migration from the Bering Sea to lagoons near Baja California, Mexico.

Off the coast of Maui, Hawaii, a humpback whale slaps the water with its broad tail.

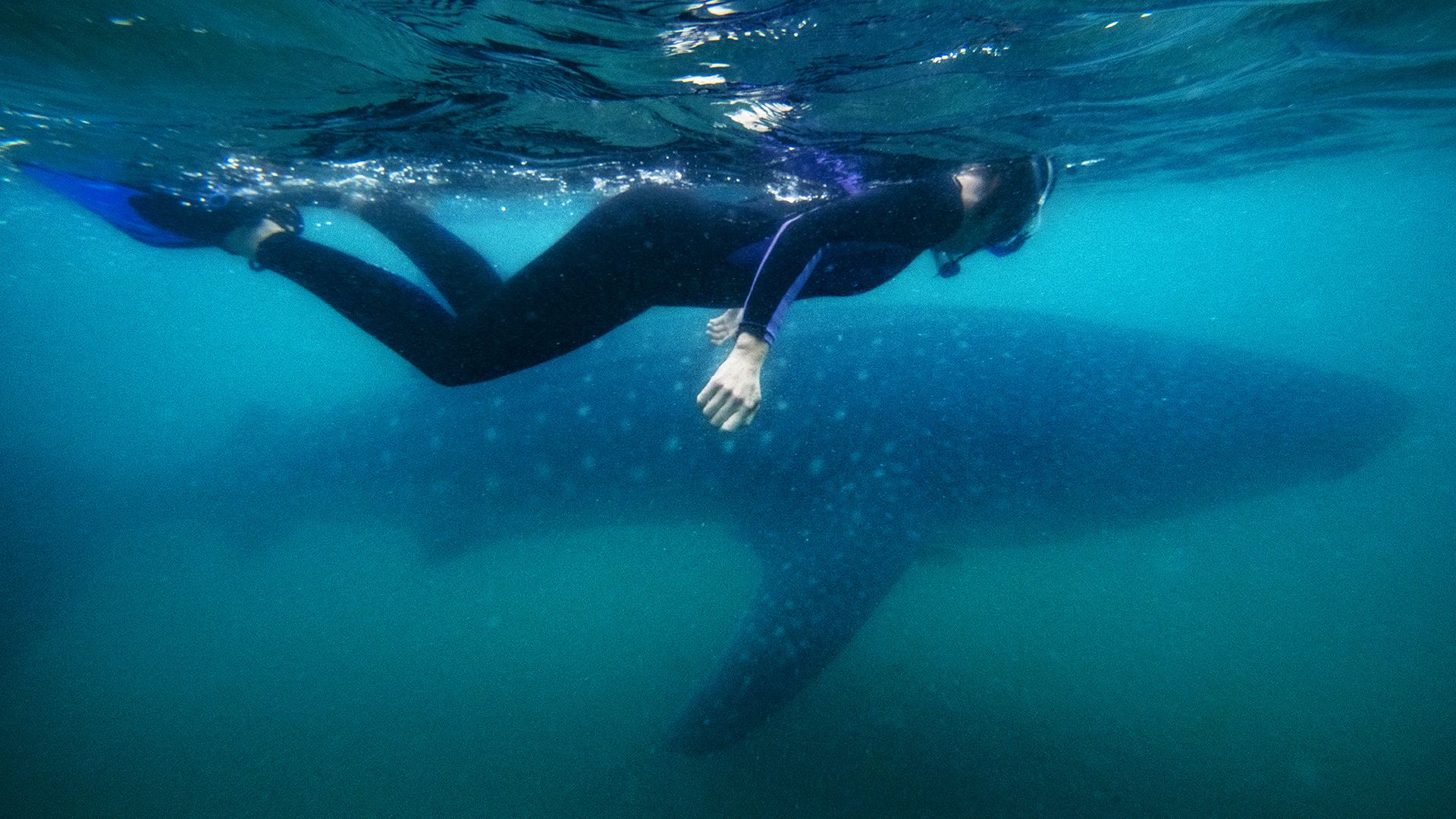

Over the decades, I’ve seen several 50-foot-long humpback whales leaping out of the water (that’s called “breaching”) and falling back with a gigantic splash. One afternoon, four male gray whales pursuing a female whale gathered directly under my boat. Another day, a fin whale suddenly lunged out of the sea with mouth agape, feeding on herring. And I’ve hugged a 30-ton gray whale that came alongside our boat in a Mexican lagoon before beginning its long migration north to the Bering Sea.

Why am I so driven to board boats large and small, year after year?

For one thing, whales have been on the planet for more than 50 million years. That’s a conservation success story, though today some of the 67 species are considered endangered. Air-breathing mammals like us, whales live underwater, and that strikes me as a huge and fascinating challenge. How do they do that?

Plus, every trip is different. In the natural world, you get no guarantees about what you may see. For me, that heightens the anticipation every time. One sunny day, on a trip to the Farallon Islands off San Francisco, in the distance, I spotted a 6-foot-tall black dorsal fin heading our way. Someone called out, “We’re going to need a bigger boat!” Forget about “Jaws.” This was a male orca, weighing as much as 12,000 pounds. Also known as killer whales, orcas are the top predators of the sea and larger than great white sharks.

When you observe whales from a boat, it can be difficult to perceive just how big they are, but the numbers command our respect. Step aside, Tyrannosaurus rex! Blue whales are the largest animals ever to live on the planet. They range from 70 to 90 feet long and weigh between 130 and 150 tons. The heart of a blue whale is about the size of a Volkswagen Beetle. Also, blue whales’ low-pitched vocalizations are among the loudest sounds on earth. A blue whale’s spout can reach 30 feet in the air, and when you first hear it, you’ll think a building exploded.

Not everything about blue whales is big. One afternoon on the back deck of a cruise ship on the St. Lawrence Seaway, another passenger pointed out what she thought was a dolphin swimming alongside the ship. That small dorsal fin she saw belonged to a blue whale, and three other behemoths were close behind.

California sea lions relax on a buoy in the Golden Gate Strait near San Francisco Bay.

Ecstatic whale watchers pet a gray whale – known as an “amistosa,” or friendly whale – in San Ignacio Lagoon in Baja California, Mexico.

On a ferry in Alaska’s Prince William Sound, I watched in awe as a humpback whale breached 42 times. Off Cape Cod, I saw a 20-foot-long whale calf nursing, a rare sight. I sat mesmerized as three female orcas swam around our motorized raft in Haro Strait, just outside Victoria, British Columbia. And off Patagonia, Argentina, I laughed out loud as a right whale calf repeatedly slid up and over its mother’s back — until she smacked it with her broad flipper.

In the U.S., federal regulations prohibit boats from getting too close to whales in the wild, but unaware of our rules, whales sometimes swim close to boats, maybe to indulge in a little people-watching. Sometimes a whale will surface next to the boat and spout, misting you with its damp breath. Hey, you’ll dry.

My longtime passion for whales also has helped me get through challenging times. When I had surgery for breast cancer two decades ago, I took a photo to the hospital of me petting a gray whale. “Cancer does not define me,” I told myself and anyone who walked into my room. “I am a whale watcher.“ More recently, after I recovered from surgery on a ruptured Achilles tendon, I savored the moment when once again I was able to board a whale-watching boat.

For almost 37 years, I’ve encouraged family members, friends, classrooms full of children and conference rooms full of adults to go whale watching. Now, I’m hoping to convince you.

Humpback whales swim off the Farallon Islands.

Related

Read more stories about outdoor adventures.

- Cumberland Connection

- Llama Trekking in New Mexico

- Weekend Getaway to Catskill Mountains, New York

- Weekend Getaway to Grand Lake, Colorado

- An American Safari

- Mountaineering in the Canadian Rockies

- Vancouver Spawns New Friendship

- Road Trip to Montana’s Independently Owned Ski Areas

- Must-Visit Mayan Ruins Near Cancun

- Weekend Getaway to Tofino, Canada

- Day Trips From Las Vegas

- Hot Air Ballooning in Arizona

- Road Trip to Hikes along the Crooked Road

- Meeting Wildlife Face to Face in the Sea of Cortez, Mexico

- Road Trip on Maine's Pequawket Scenic Byway

- Road Trip to Whale Watch Spots

- Isle Royale National Park

- Weekend Getaway From Mexico City to See Butterflies

- Visiting Washington's Olympic National Park in the Offseason

- South Dakota Black Hills

- Icefields Parkway 3-Day Driving Trip

- Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness

- Road Trip to Colorado Mountains Fourteeners Attractions

- Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park

- Sinkholes and Underwater Caves Rival Tulum’s Caribbean Beaches

- Weekend Getaway to Palo Duro Canyon, Texas

- Todos Santos: A Colorful, Seaside Town in Mexico

- Weekend Getaway to San Luis Obispo

- Southern Illinois Road Trip Features Hidden Gem Outdoor Adventures

- Road Trip to Snowy Range Scenic Byway

- Road Trip to Saguaro National Park

- Algonquin Park Scenic Drive

- Tour Mexico’s Río Secreto, an Underground River

- Road Trip to Wyoming's Flaming Gorge

- Nature Photography Tips

- Glamping in the Catskill and Adirondack Mountains

- Stargazing in Texas: McDonald Observatory and Beyond

- Road Trip to Canyon de Chelly National Monument

- Road Trips to See Wildlife

- Kenai Fjords National Park

- Every Hour Is Golden in Mexico’s Loreto

- Road Trip to Red Rock Canyon Near Las Vegas

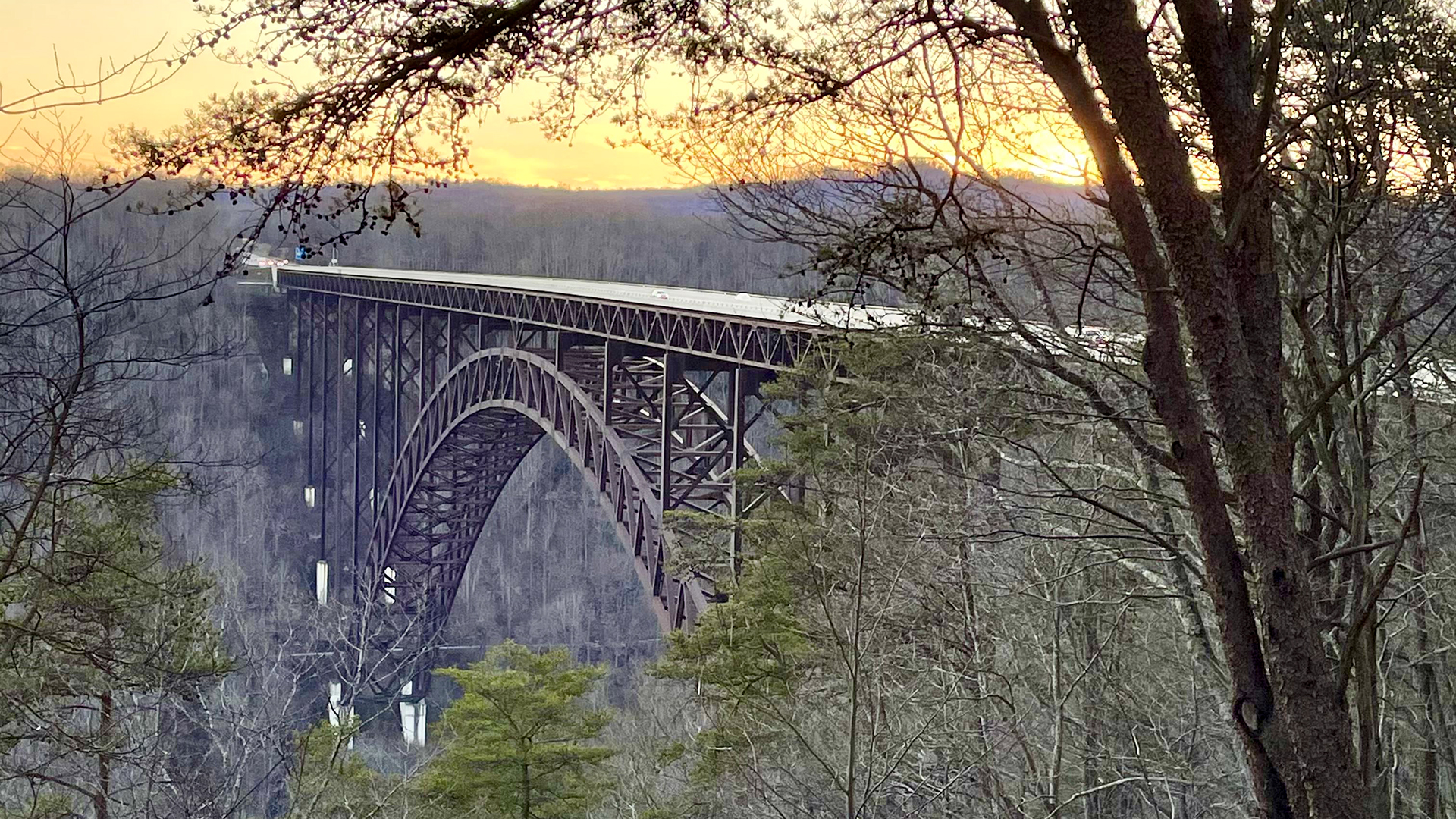

- New River Gorge National Park

- Road Trip for Florida Fishing

- Romantic Getaway in Sedona, Arizona

- Road Trip on the Berkshire Cheese Trail

- Road Trip to See Whales

- Road Trip to Colorado Mountains Fourteeners

- Grand Canyon Hike

- Glamping in Oregon

- Coquihalla Mountain Skiing

- Old Friends Drive the Sea to Sky Highway

- Floating on Ozark Rivers

- Crater of Diamonds

- Caving in the Black Hills of South Dakota

- Great Smoky Mountains Waterfalls

- Hunting for Wild Mushrooms in Indiana

- Road Trip to Nova Scotia's Wild Berry Bounty

- Washington's San Juan Islands